Bayesian Inference of Star Formation History in the Host Galaxies of Tidal Disruption Events

For the better part of the past two years, I have done a lot of thinking about galactic nuclei. At the centre of every distant galaxy and our own, there is a supermassive black hole. Some are stealthy, emitting little to no light which we can detect. A rare fraction of these black holes, so called active galactic nuclei or AGN, devour unfathomable quantities of stellar and interstellar matter and in doing so, shine more brightly than their entire host galaxy. Most recently though, I have been thinking about a slightly less spectacular nuclear event: a tidal disruption event.

These occur when a single star makes a close orbital approach of an otherwise quiet or “quiescent” black hole. Tidal forces on the star rip it apart. Some material falls into the black hole and the rest is jettisoned on a wide orbit. This process produces a brief but intense increase the nuclear luminosity, which then fades over a matter of days to months.

In September 2020, I was given access to the spectra and photometry for eight galaxies which have hosted tidal disruption events within the past few years. With this data, I wanted to investigate whether the host galaxies of these events shared a statistical property of AGN hosts: the tendency to be “post-starburst”.

The most recent component of star formation is referred to as a “starburst”—a short period of abnormally high star formation which occurs long after most of the stellar mass in a galaxy is formed.

The Starburst-AGN Connection

For decades, a correlation between nuclear activity in distant galaxies star formation in those galaxies has been emerging. Many AGN have host galaxies with atypically blue spectra, indication recent star forming activity (more on that in a moment). There is a tight relationship between total stellar luminosity and black hole mass. In other words, and positive correlation between star formation and black hole accretion.

The XSHOOTER Data

| TDE | m | z |

|---|---|---|

| ASASSN-14li | 15 | 0.0206 |

| ASASSN-15oi | 16 | 0.0484 |

| AT2018fyk | 17 | 0.06 |

| AT2019ahk | 17 | 0.026211 |

| AT2019azh | 15 | 0.022 |

| AT2019dsg | 15 | 0.0512 |

| AT2019qiz | 15 | 0.01513 |

| iPTF16fnl | 16 | 0.018 |

| AT2018hyz | 17 | 0.04573 |

| ASASSN-14ae | 17 | 0.0436 |

Do the host galaxies of TDEs have the same properties? Above is a small table of them, and as you can see, they are all similarly of low magnitude and moderate redshift. Because they are all at redshifts <0.1, we can say that they are approximately the same age as our own Milky Way.

At these distances, they occupy very little real estate on a CCD, but the XSHOOTER instrument on the Very Large Telescope provides us with very high resolution spectra from these objects.

The BAGPIPEs Module

To investigate whether or not the host galaxies of transient tidal disruption

events exhibit the same statistical behaviour as those of AGN, I employed the

BAGPIPEs Python module to determine by Bayesian inference the star formation

histories of the TDE hosts from their spectra.

BAGPIPEs has two main functions. First, it allows you to define the functional form of a simulated galaxies star formation history, in stellar mass formed per unit time, over the history of the universe. From that prior, it can simulate that galaxy’s spectrum as it would appear to us in the present day.

It can also do the inverse: take in a real, observed spectrum from a galaxy and infer from this a distribution of posterior star formation histories. It does this using stellar population dating, whereby the ratio of flux from massive blue stars is compared to that from less massive red stars to make assumptions about when the stellar population formed.

The reason this works is because very massive, blue stars live much shorter than their smaller counterparts, so galaxies with a high number density of blue stars necessarily must have had recent star formation. The problem with this is that stellar lifetimes increase dramatically with small decreases in initial mass. So the number O- and B-type stars in a given galaxy can give you detailed information about the past billion years of star formation. But while the next smallest A-type stars are on the main sequence, it’s difficult to determine whether they were formed a billion years ago or three billion. As you go down the spectral classification types, the problem only gets worse.

Selecting Physically Reasonable Priors

So in order to get reasonable SFHs out of BAGPIPEs, one has to make some assumptions about what the SFH looks like. In some cases, models which are inconsistent with observations over various redshifts may fit the spectral data “better” than a more observationally consistent model, and it’s important that these are excluded from the possible solutions.

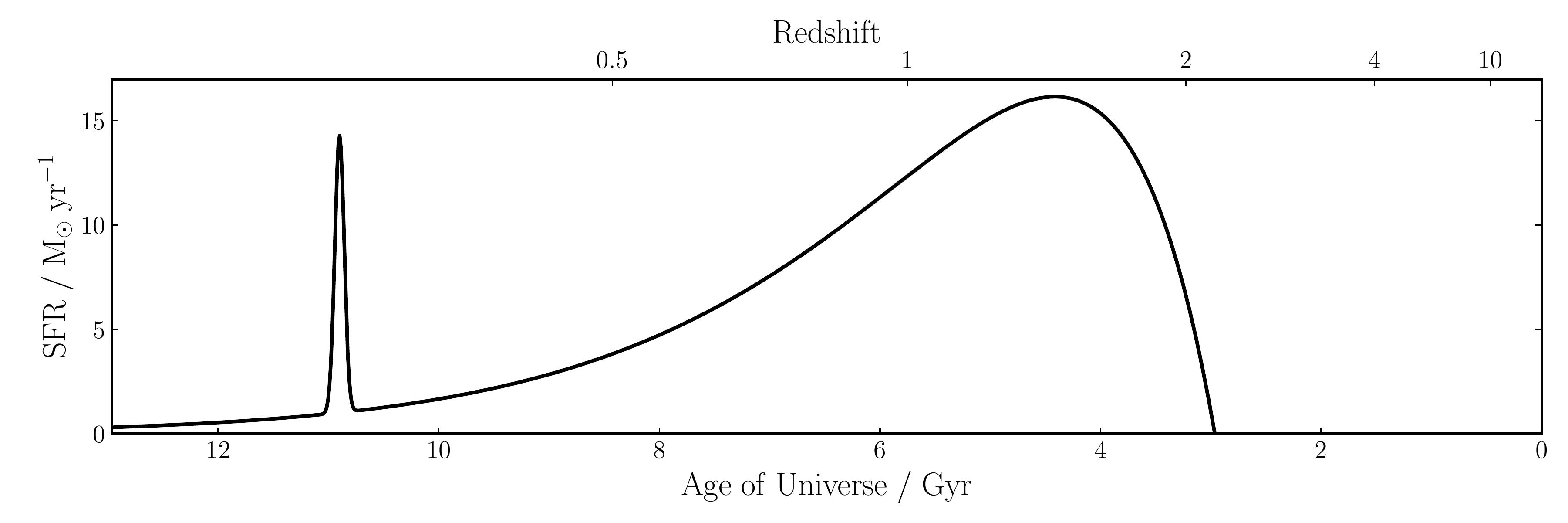

As we peer into the cosmos at high redshift galaxies, we find that star formation actually peaks at a time called “cosmic noon”, around redshift 3-4. If I insisted that this be the case in my posterior star formation histories, perhaps I could avoid the erasure of the burst component in the fit.

R4: Fixed Old Component, Free Burst Component

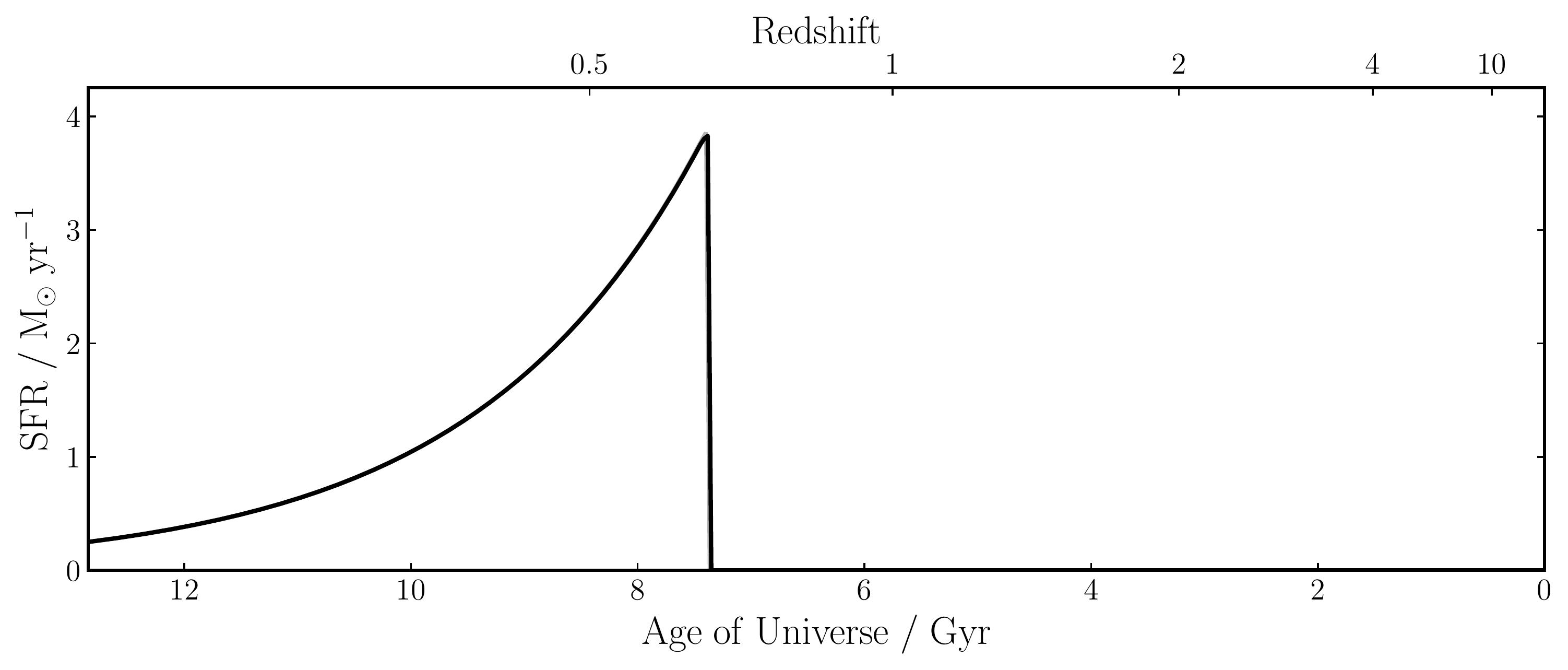

With that in mind, I devised a set of priors, insisting that most of the stellar mass be formed in an earlier era, and letting the burst float freely over the parameter space. If a non-zero burst mass was detected, I could reliably infer the existence of young, high mass stars in the host. If the burst mass was found to be near zero, then the stellar population must be old indeed.

Blind Fitting Results with R4 Priors

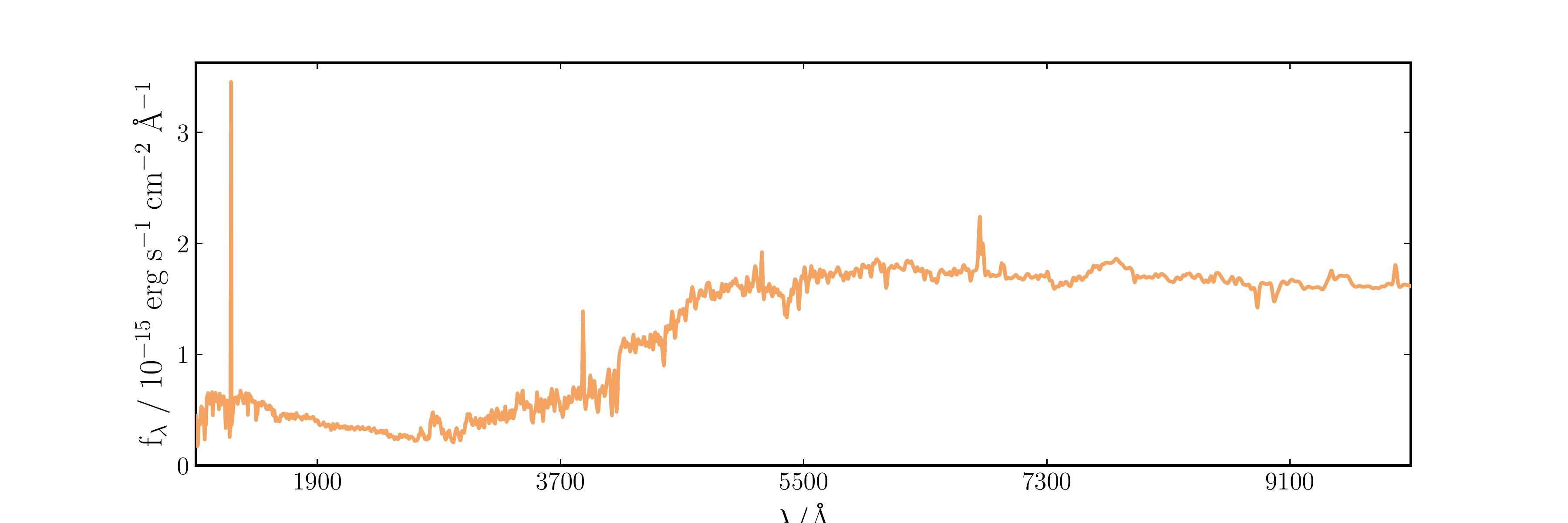

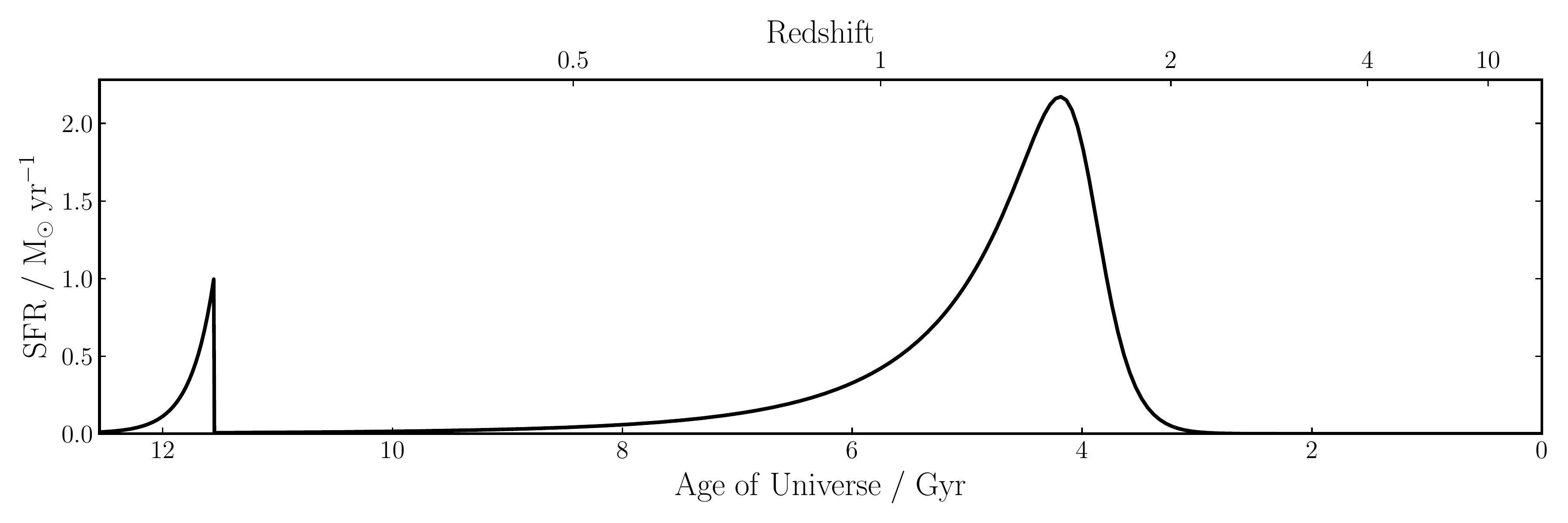

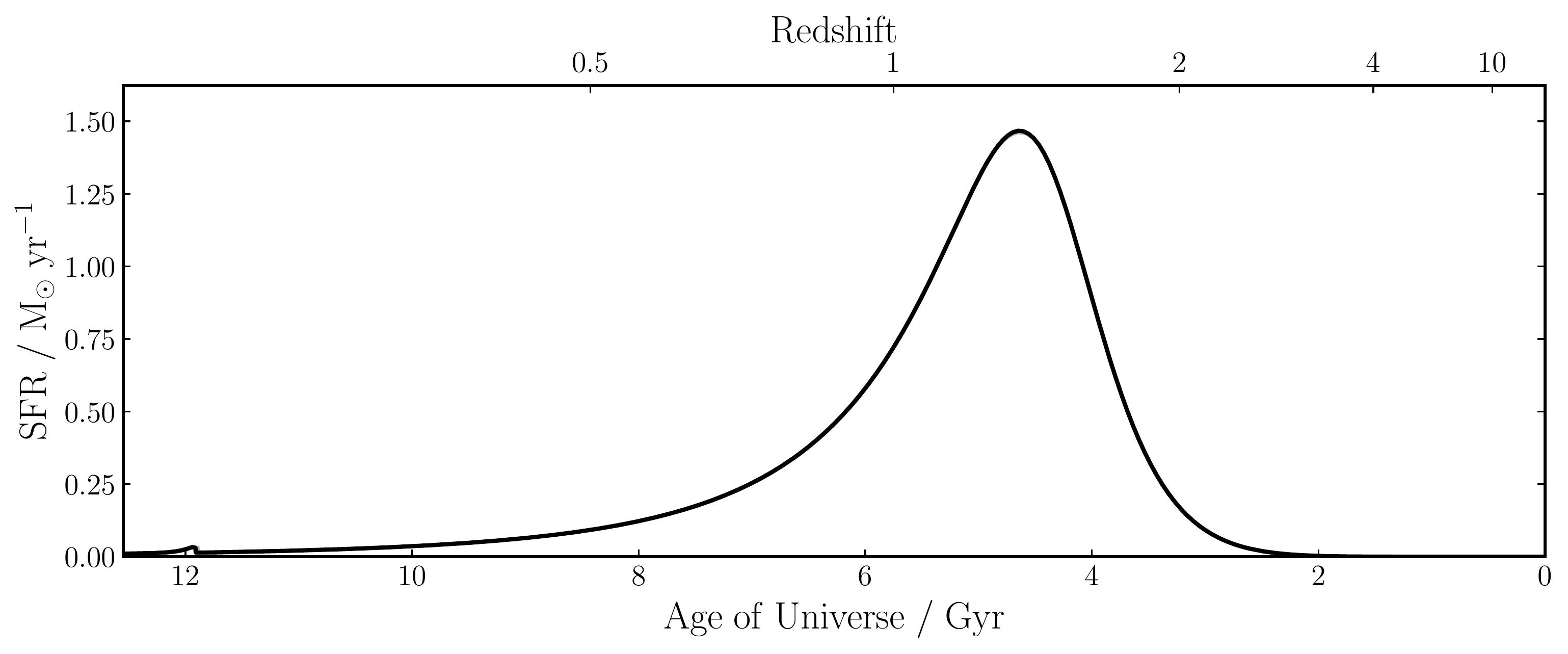

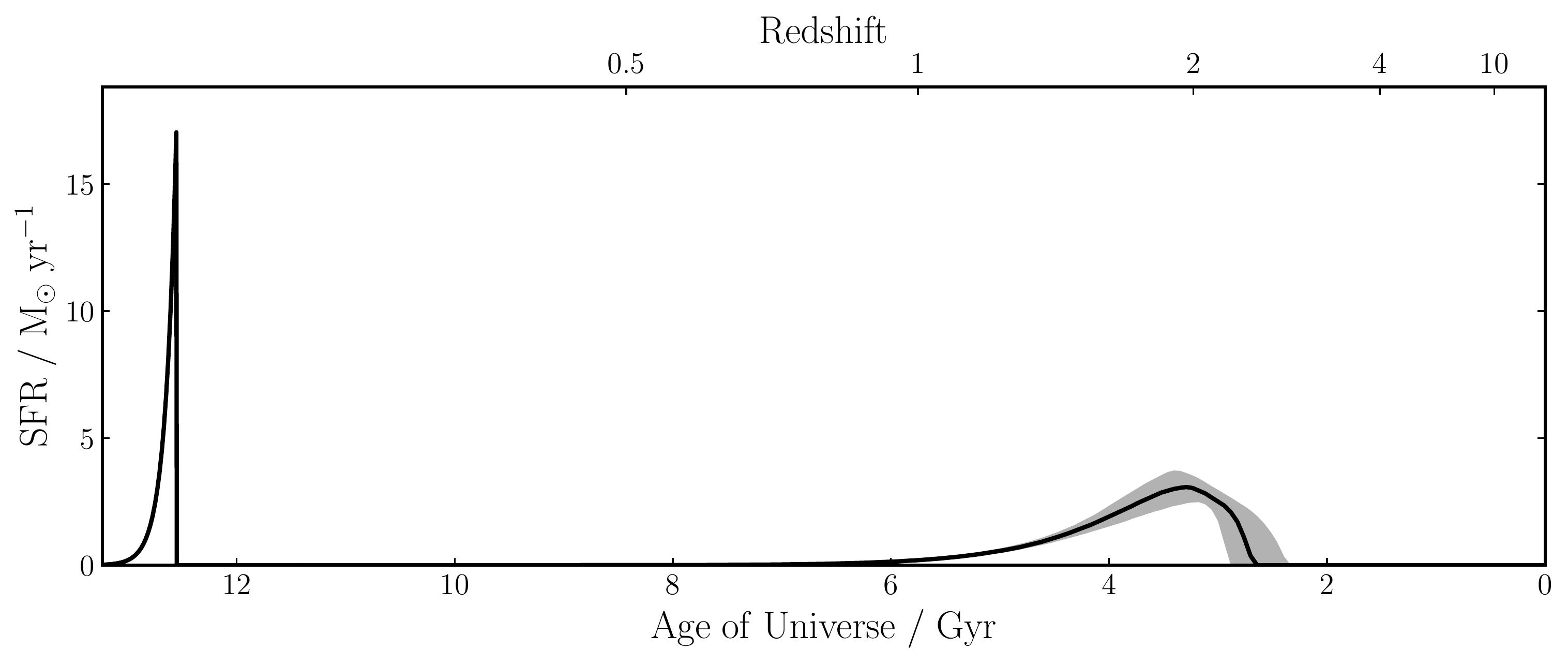

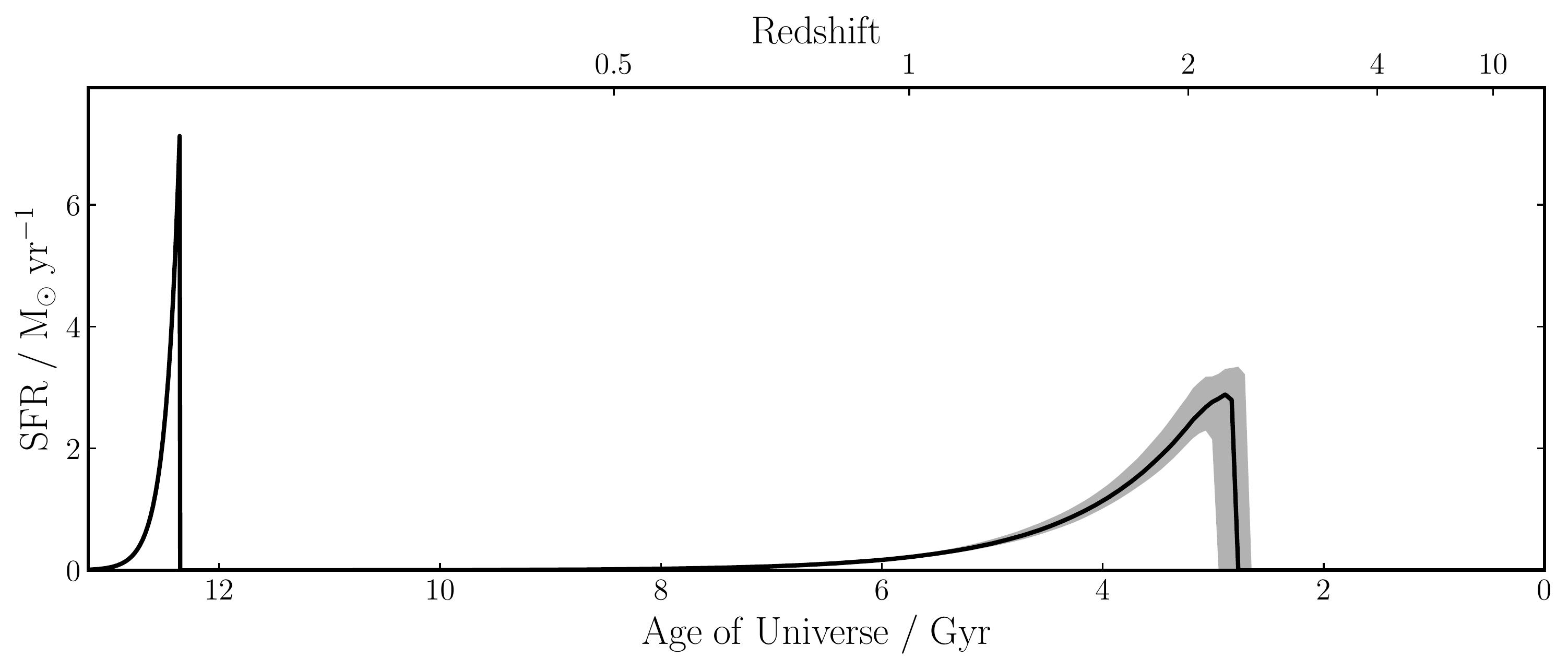

Finally, I began to successfully detect the starbursts. Here you can see one such “blind fit”, with the “true” SFH on top, and the fitted one on the bottom. When a burst of sufficient mass is present in the prior, it detects them, although sometimes it struggles to pin down the age of bursts older than 3 billion years. Importantly, fitting with these priors doesn’t give false positives. When there is no burst in the prior, it doesn’t show up in the fit either.

Very low mass bursts are sometimes missed. Bursts of moderate mass (around 10^8 solar masses) are detected, but their mass sometimes underestimated, as you can see above. I thought this might be due to the fit favouring longer decay times for older component, so that some blue stars are accounted for by ongoing formation instead of the burst. Upon investigation though, I found that the old component decay time and burst mass were not very strongly correlated, so the reason for mass underestimation still merits some study.

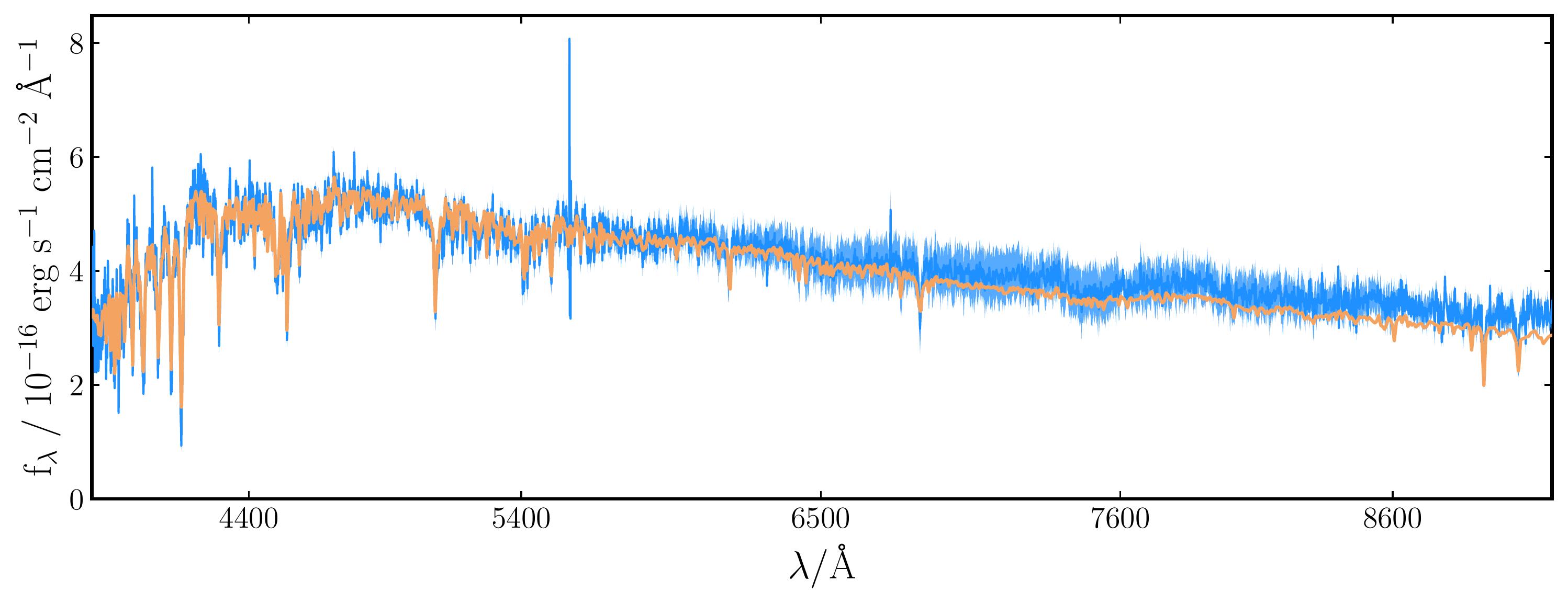

Application to XSHOOTER Data

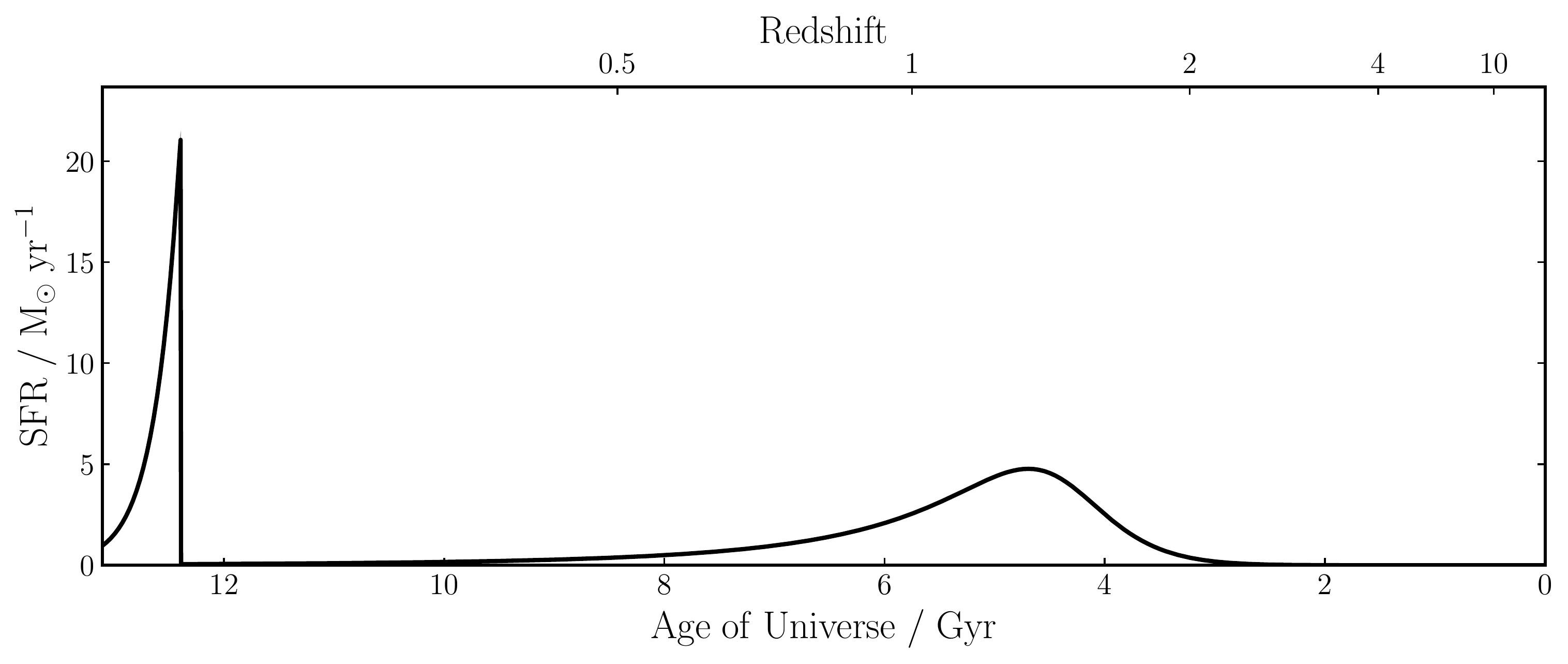

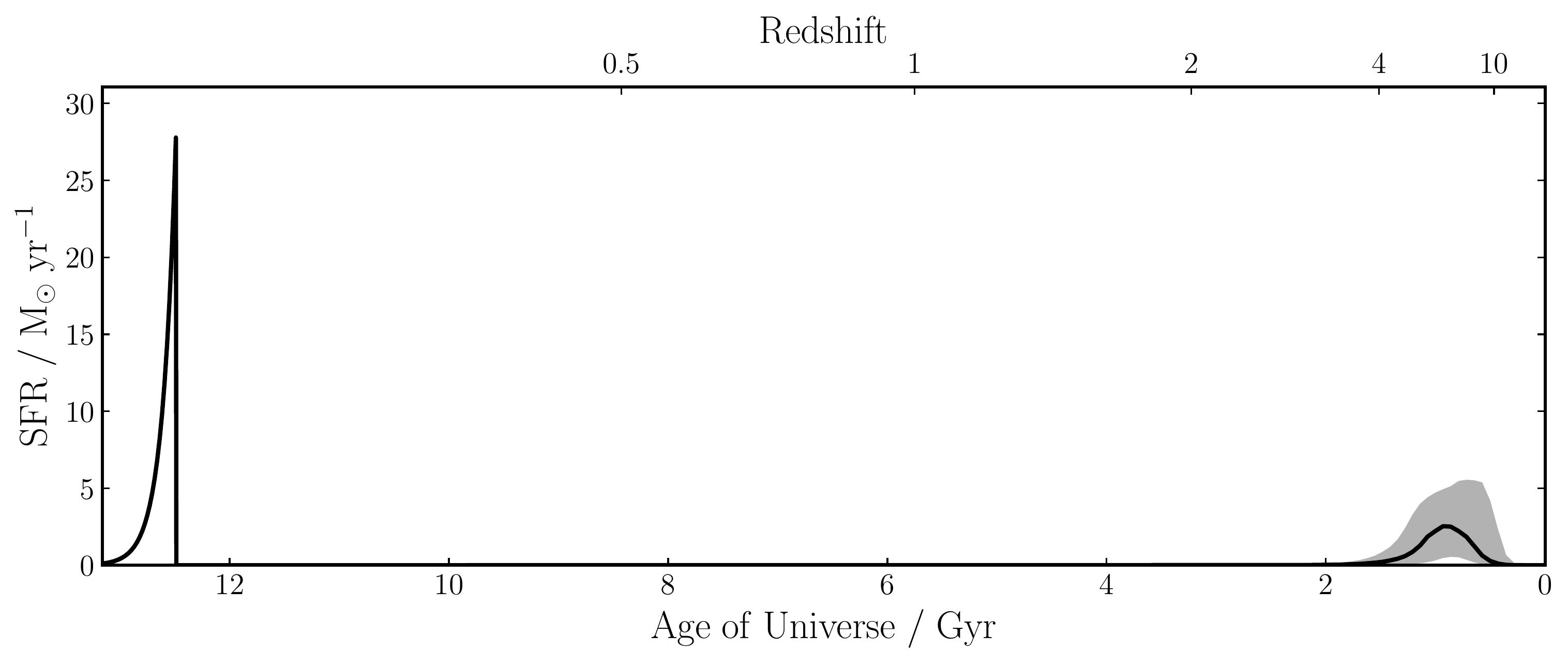

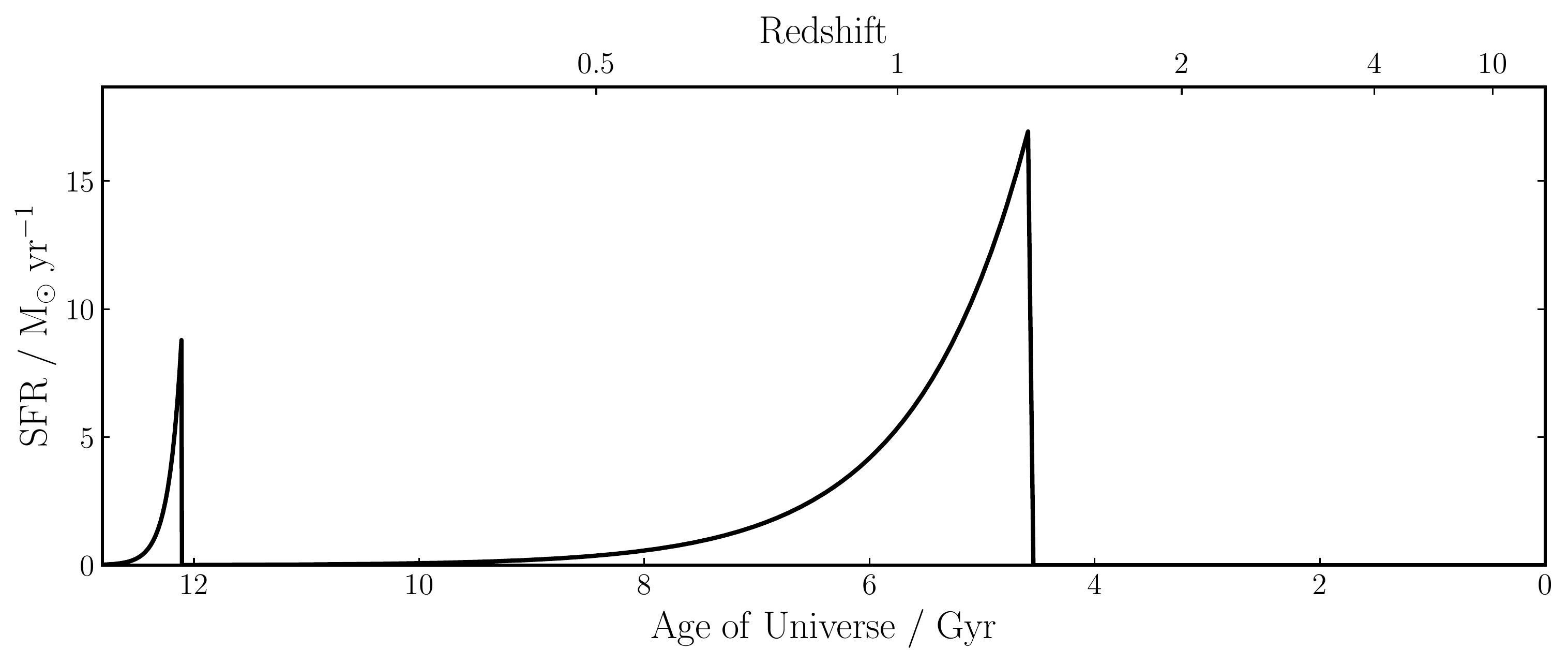

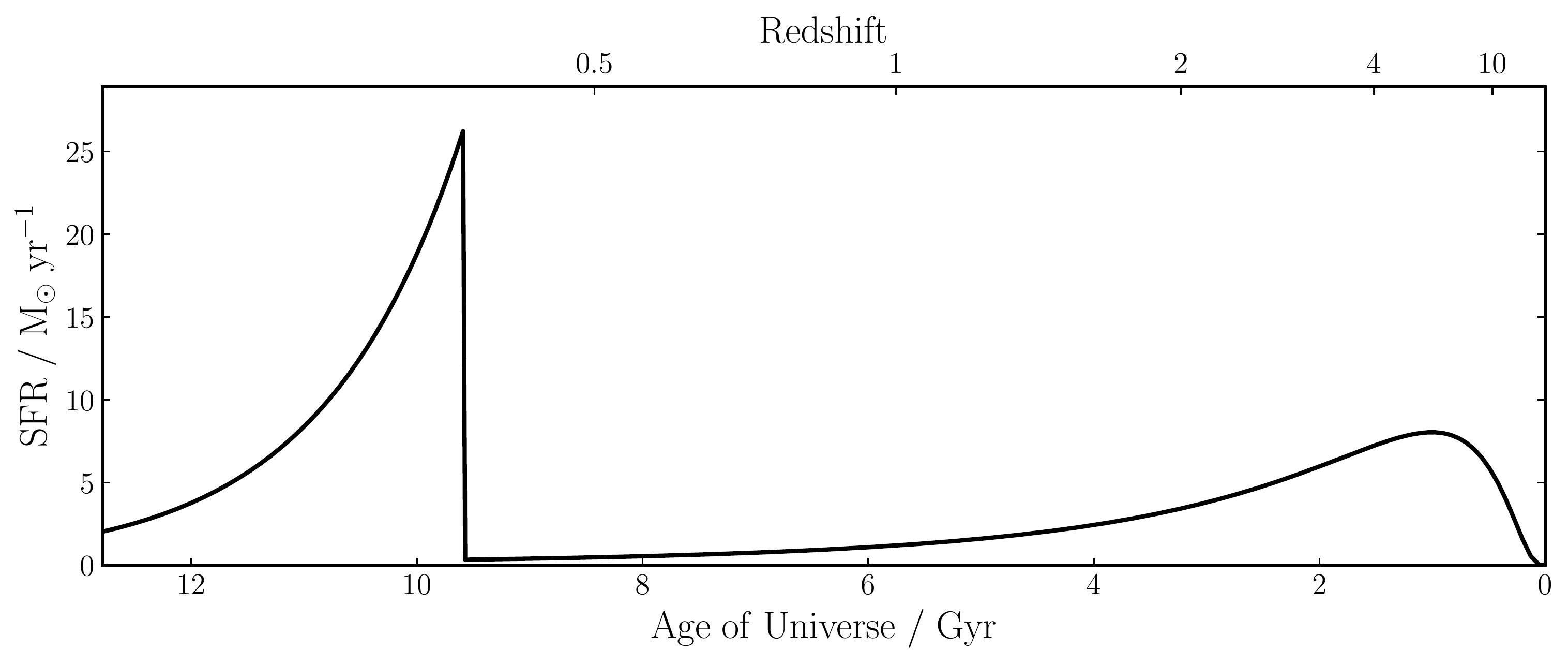

Now confident in the reliability of fits performed with these priors, I turned BAGPIPEs on the TDE data, which of course has no “known” SFH. Here are some of my results:

As you can see, the TDE hosts exhibit strong evidence of recent starburst activity, with star formation rates much higher than the typical ambient rate of 2-3 solar masses per year. Almost all of the fits find old components which are consistent with observational evidence for star formation at cosmic noon, and with burst components consistent with present day starburst galaxies. This is a compelling reason to believe they are representative of the “true” star formation history of these hosts.

Conclusions

It seems that starburst activity in the past 3 billion years of a galaxy’s history is inferable with some reliability, given that certain assumptions about what constitutes a physically realistic SFH are made. With that in mind, I’ve applied this to the spectra of several TDE hosts, and found that they indeed seem to share the statistical behaviour of AGN.

With that said, it’s important to note that eight samples available to me for this project are not nearly a large enough sample size to draw this conclusion. This “proof of concept” has applications for larger research projects, and it would certainly be valuable to apply fits with the R4 priors to larger sample size, with priors more carefully tailored to host morphology, and to compare these results to quiescent galaxies with similar morphologies.